Bad Science Journalism- Intermittent Fasting and Cardiovascular Death?

Widespread coverage of a not-yet published study on intermittent fasting highlights why journalists and mainstream media are terrible at covering science.

As of now many of you have likely come across some rather damning headlines such the ones below:

It’s not hard to find articles embracing this alleged new study since it would upheave this new growing dietary trend. Imagine if many people who are trying intermittent fasting may be at risk of cardiovascular-related death, especially with an increase of nearly 91%!

So of course, such a study with such findings will grab people’s attention and explains why this study seems to be widely circulating.

The only problem is that these comments aren’t from a published study but rather a conference put out by the American Heart Association during their Epidemiology and Prevention/Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health Scientific Session that is going on this week.

That is, the information from this conference has not been published yet meaning that no in-depth information is available online, begging the question of why so many news outlets have taken to reporting on these findings as if they are definitive.

How exactly can outlets cover a study when there is no study to cover? And where exactly would they even get this information?

This is one of the many problems I have with mainstream outlets- they aren’t likely to actual read and discern information themselves but are likely just parroting information they found without doing so much as the providing basic scrutiny of studies. And it’s a growing problem where people who report on science are generally not scientifically minded and able to parse out what may be bs and what may be good data and methodology.

It's one of the reasons why I generally don’t look to news outlets when it comes to learning about a new study. They do, however, serve as a good gauge to see how much one can butcher, misrepresent, or over-extrapolate from a study.

Returning to the issue at hand, it’s likely that many outlets have either taken to reporting on a news release put out by the AHA as a means of gaining information from the study, but even this acts a second-hand account that doesn’t tell us much about the actual methodology but only the findings:

The analysis found:

People who followed a pattern of eating all of their food across less than 8 hours per day had a 91% higher risk of death due to cardiovascular disease.

The increased risk of cardiovascular death was also seen in people living with heart disease or cancer.

Among people with existing cardiovascular disease, an eating duration of no less than 8 but less than 10 hours per day was also associated with a 66% higher risk of death from heart disease or stroke.

Time-restricted eating did not reduce the overall risk of death from any cause.

An eating duration of more than 16 hours per day was associated with a lower risk of cancer mortality among people with cancer.

This is probably why most articles have repeated the information listed above. They likely just copied-and-pasted the information over from the news release.

And this is, again, why we need more people who can discern and scrutinize things that don’t seem right and realize that some science may just be bad science.

For instance, although the study isn’t printed yet look at the abstract available online:

Participants aged at least 20 years who completed two valid 24-hour dietary recalls and reported usual intake in both recalls were included from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey in 2003-2018. Mortality status as of December 2019 was obtained through linkage to the National Death Index. An eating occasion required consuming more than 5 kcal of foods or beverages. Eating duration between the last and first eating occasion was calculated for each day. The average duration of two recall days defined typical eating duration which was then categorized as <8, 8-<10, 10-<12, 12-16 (reference group; mean duration in US adults), and >16 hours. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards models were employed to estimate the association of eating duration with all-cause and cause-specific mortality in the overall sample and among adults with cardiovascular disease or cancer. Adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were derived.

Can you figure out an issue with this study?

This study categorized people into different “eating duration” groups based on only two surveys of 24-hour dietary recalls.

Readers should note that most participants in a survey are not likely to be honest, are likely to respond with heavy biases such as providing answers they believe the researchers want or downplaying things that would not put participants in a good light. It’s one of the reasons why I’m generally skeptical of survey-based studies because people tend not to have the best memory or will attempt to be honest.

But the real kicker here isn’t the possibility of a heavy bias from the surveys, but the fact that researchers believed that only two surveys were enough to gauge people’s typical dietary eating habits and eating durations years into the future. Two days out of 365 days in a year hardly amounts to much already, and there can be a whole list of reasons as to why someone may have the type of eating durations that they had during the time of the survey.

It may not be diet alone but scheduling, complications with eating, and really a host of many different variables that may have affected the eating durations during the time of survey completion. It’s one of the reasons why we are taught that you cannot create a slope from two data points alone- the more data the better of a guess you can make.

And it’s also why this measure can’t make any estimates of long-term eating durations because the authors themselves can’t know what the actual participants’ typical eating durations are and extrapolate from there possible behaviors in the future. They most certainly can’t determine if people still have such eating durations near the time of their passing.

Now, there is this line that is leading to a bit of confusion:

An eating occasion required consuming more than 5 kcal of foods or beverages. Eating duration between the last and first eating occasion was calculated for each day.

Five thousand calories are already excessive for one day, and so it would certainly be far too much for one meal!

However, my suspicion is that this is likely a difference in units. Note that most of the calories listed on products in the US are actually kilocalories (hence the capital “C” on products to infer kilocalories), and so the “5 kcal of foods or beverages” may just mean the very first instance you have calories, which itself is still a strange measure because I’m not sure how many people would be aware that they have eaten 5 calories or would even be able to recall the calories of some of their items.

It’s curious why the authors don’t provide any information on what the participants ate- isn’t what people ate just as important as the time that they ate?

So overall there are a lot of problems with this study. The methodology in categorizing participants should heavily be scrutinized- can you really tell people’s eating habits from only two surveys, and can you really assume that these eating durations are still going on for years?

And even if you could, no reason is provided for why people may commit to such a limited window of eating. It’s likely that some of these people are at-risk of diseases already, which would then be a case of reverse causality- it’s not the restricted eating that led these people to have increased risk of cardiovascular mortality, but that their greater risk of cardiovascular mortality may have led them to try alternative diets. One of the problems is that the study doesn’t appear to provide any information on people’s background history so we can’t make any judgement on why they would try intermittent fasting. One would think that this would at least be something worth asking participants.

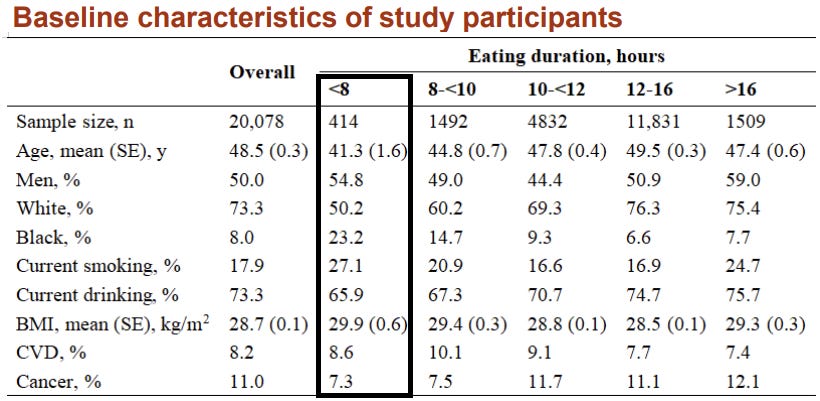

Interestingly, the researchers’ poster which noted baseline characteristics does appear to show more smokers in the “fewer than 8 hours group”, and it’s worth noting that this group is far smaller than any of the other eating duration groups:

But again, this data is not worth much without any additional context.

So, when looking at this report one must wonder why this is spreading like wildfire. Hardly any information is available about this study, and even the available information is highly questionable.

And yet journalists have been so quick to cover this study as if it is the death knell for intermittent fasting, and that’s likely why this study is receiving so much widespread attention.

It’s for the mere fact that the premise provides for a lot of attention, clicks, views, whatever. It’s the pinnacle of clickbait and one of the reasons why we need more people to be critical of the information that they read.

Try looking for primary sources, consider how researchers got their results and whether it seems plausible, and engage with better critical thinking skills.

Not all science is good science, and we need more people who are able to tell the difference.

In addition…

I meant to cover this paper a few days ago but got busy at work and didn’t have time. In the meantime, Bret and Heather covered this study yesterday, as well as another study from that same conference published in the Daily Mail alleging that even one day of sunbathing can be harmful:

This study appears to suffer from the same egregious mistakes as reporting on the intermittent fasting study. Again, this is a clear example of how people may report on studies without actually understanding what they are reporting.

For Bret and Heather’s coverage here’s their livestream from yesterday starting at the pertinent point:

Another study for reference

This study also reminded of a previous study that I covered. This one was published in early 2023 and it tied the consumption of ultra-processed to increased risk of mortality including death from certain cancers:

Ultra-processed foods and cancer?

Modern Discontent is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber. Cover image from MyRecipes with credit to MUKHINA1/GETTY IMAGES

Although the premise may be sound (i.e. ultra-processed foods are inherently bad) it doesn’t reach its conclusions given the fact that it relies on the same methodology as the intermittent fasting study whereby 24-hour dietary recollections were collected 5 times over 3 years from participants. In fact, most of the participants didn’t even fill out all 5 surveys, and in reality more than half filled out at most 2 of the surveys!

We can see how this study itself already suffers from the same issues as the intermittent study, but in this case using an otherwise assumed conclusion that ultra-processed foods are bad. It’s an example of how an otherwise sound conclusion doesn’t mean that researchers were able to reach that conclusion soundly.

If you enjoyed this post and other works please consider supporting me through a paid Substack subscription or through my Ko-fi. Any bit helps, and it encourages independent creators and journalists such as myself to provide work outside of the mainstream narrative.

Looks as though the media has been casting about for any possible explanations for the extra cardiovascular problems that seem to be popping up lately. Grasping at any straws. Wonder why……

Taking our health into our own hands i$ a big 'no-no' don'tchya know?